Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math form the STEM college majors. STEM careers take off in many directions and provide many opportunities for a college student to develop their interests. And, importantly, these majors and careers are no longer a “boy’s only” club. The number of female STEM undergraduates is growing every year, and in some colleges nearly half of the students majoring in engineering are women. In this post, The STEMwinder offers some of the historical reasons why STEM is trending this way, how female high-school students can channel their interest in science and math into a fulfilling college major, and ways that adults (men and women, whether in a STEM career or not) can help young women succeed in STEM professions.

The history of women in STEM

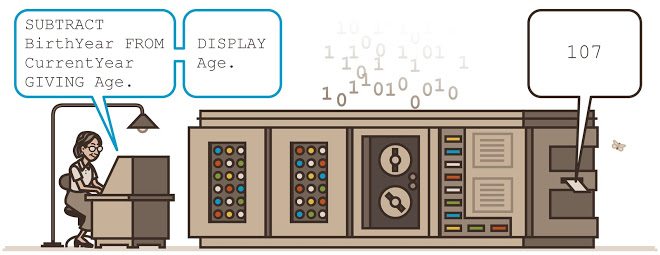

Turning back the clock to 1934, the future Admiral Grace Hopper earned her Ph.D. in mathematics at Yale. She would go on to be instrumental in designing and building computers such at the Navy’s Mark 1 computer, where she joined the new team building it in 1944; years later in a speech at Ohio State University, Admiral Hopper was introduced as “the third programmer on the first computer in the US.

She became the first person to debug a computer when she repaired the Mark 2 computer by removing a moth that had gotten into one of the 760,000 electromechanical gadgets that made the five-ton computer work. Admiral Hopper went on to create the first compiler for computer languages, and developed the foundation of the Cobol computer programming language used in thousands of business application, and the Fortran language which became a primary science and engineering tool (and, incidentally, the first high-level language the STEMwinder used as an undergraduate engineer). The Admiral’s 107th birthday was recently commemorated in a Google Doodle.

Fast forward to today, and high-school women can see role models in some of the most traditionally all-male professions. Astronauts have a special place in the constellation of STEM professionals. A shuttle mission demands a multidisciplinary approach because every astronaut needs to carry out multiple jobs during the intensely concentrated time in space. In its early days NASA was full of “the right stuff”, and now there are many female scientists and engineers contributing to advances in space flight. Some of the female astronauts in the NASA space shuttle program:

Dr Mae Jemison is an engineer, physician, astronaut, educator and innovator. Dr. Jemison was the science mission specialist on STS-47 Spacelab-J (September 12-20, 1992). She has two STEM college degrees: a bachelor of science degree in chemical engineering from Stanford University, and a doctorate degree in medicine from Cornell University.

Ellen Ochoa, Ph.D., received a Bachelor of Science degree in Physics from San Diego State University in 1980, and a Master of Science degree and Doctorate in Electrical Engineering from Stanford University, Having formerly been director of flight operations at NASA she is now director of the Johnson Space Center.

Dr. Sally Ride, the first American woman to fly in space, was finishing her Ph.D. in physics at Stanford University in 1977 when she saw an article in the student newspaper saying that NASA was seeking astronaut candidates, and that for the first time, women could apply. When she blasted off aboard the space shuttle Challenger on June 18, 1983, she became the first American woman in space.

Why role models are important (for future STEM students):

A 2012 report by the Congressional Joint Economic Committee said that only 27 percent of those working in computer science and math positions are women. Writing in The Hechinger Report, Madison Cox, biomedical engineering undergraduate at Columbia University, noted “I was not born with intrinsic knowledge of math or science. My success has a much simpler explanation: Whenever I doubted my abilities, I had teachers and parents who supported me.”

Dr. Margaret Leinen received her doctorate in oceanography from the University of Rhode Island (1980), her master’s degree in geological oceanography from Oregon State University (1975), and her bachelor’s degree in geology from the University of Illinois (1969). Karen Flammer, the director of education for Sally Ride Science@UC San Diego presented a video interview with Dr Leinen on how she got started in her STEM career.

A college campus with a proportional female presence in the STEM classroom is important in both recruiting women to attend and enroll, and in providing a supportive and reinforcing environment in and out of the classroom. And here, the news is mostly good: The Washington Post reported that women earned a majority of bachelor’s degrees in engineering in 2015 at Olin College of Engineering (53 percent, and at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (51). Women netted at least 40 percent of engineering degrees that year at Yale (49 percent), Howard (45), George Washington (43), Harvey Mudd (42), Brown (41) and Southern Methodist (41). Nearly half of Dartmouth engineering majors are women, and a quarter of the University of Illinois College of Engineering are women. Dr. Pamela Norris, associate dean for research and graduate programs at the University of Virginia’s engineering school, said the university has had a solid share of women in engineering for many years. She hopes women will make up at least a third of the students in every engineering specialty, enough so they do not feel self-conscious in class. Exactly what share constitutes a critical mass can vary, but it need not be 50 percent. Dr. Norris earned a Ph.D. Mechanical Engineering in 1992 at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

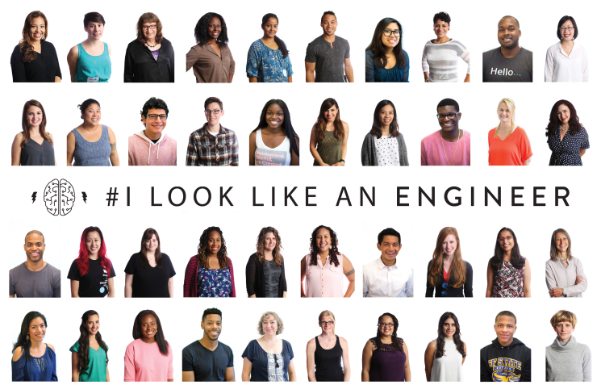

In August last year a new hashtag was trending on Twitter: #ILookLikeAnEngineer. What’s up with that? Michelle Glauser, a software engineer and startup entrepreneur, created an ad campaign and hashtag to support awareness and inspiration of non-stereotypical engineers. With crowdsourced funding on indiegogo, billboards started showing up in San Francisco. Michelle recently wrote about the success of the campaign.

What can parents, educators, and counselors do to help?

Edie Fraser, founder and CEO of Million Women Mentors, has assembled an impressive collection of experts and supporting organizations to provide mentoring to young women interested in STEM. In a recent white paper, MWM writes that High-quality skills-based mentoring and sponsorship programs that connect girls and young women with STEM professionals can significantly increase the number of women who pursue and succeed in STEM fields. There are many resources available to assist in setting up an effective mentoring program for young women. A useful starting point is the Million Women Mentors’ Elements of Effective Practice for Mentoring(TM) which provides “program practices and relationship strategies that facilitate meaningful mentoring relationships and positive outcomes for youth and adult participants.” Interestingly, the benefits of mentoring for STEM women carries forward into professional careers; the National Academy of Sciences found that “In chemistry, female assistant professors with mentors had a 95 percent probability of having grant funding compared to 77 percent for those women without mentors. Over all six fields surveyed female assistant professors with no mentors had a 68 percent probability of having grant funding compared to 93 percent of women with mentors.”

Recursively, there is scientific evidence proving that a gender bias against women exists in STEM education. Research at the University of Washington showed that by the time girls get to high school, the belief that they are less talented in STEM is already ingrained; as early as second grade, children in the study demonstrated the American cultural stereotype that math is for boys.

Positive reinforcement to aspiring female STEM students doesn’t have to be complicated. NASA found that simply showing visual representation of women in STEM is helpful, recommending that organizations working for NASA show “gender diversity in the visual images displayed in communications materials and publications”. Dr. Jelena Kovacevik, head of the electrical and computer engineering department, noted in the Washington Post that small gestures can make a larger point. When she is running a meeting, she typically asks a male colleague to take notes, pushing back against the notion that secretarial tasks should go to women. Dr. Kovacevik earned her doctorate in electrical engineering from Columbia University in 1991.

I’m a guy—why should I care?

Organizations and companies that hire STEM graduates benefit from diversity in every dimension, including gender diversity. Look at it this way: since women are about half the population, hiring women into STEM jobs doubles the number of qualified candidates and raises the overall quality of scientific research and engineering solutions. And for examples of the kind of female professionals you will encounter in the world of STEM careers, take a look at this video from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

Recently, the Washington Post just published an article about this, and released all the stats from many universities across the nation. It is actually fascinating piece that I recommend to you all. Thanks to Kiersten Murphy @collegeadvisors for finding the article.